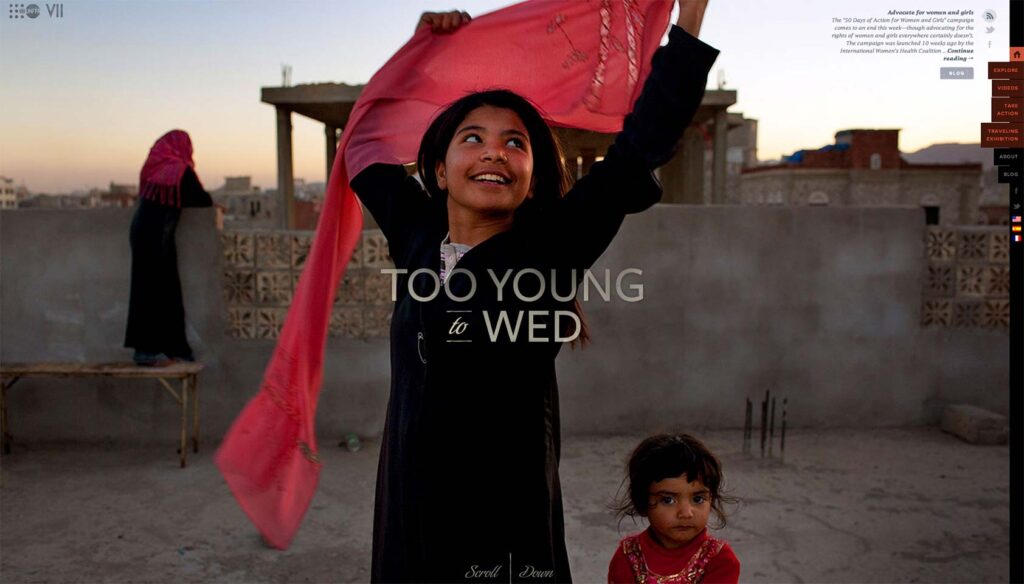

Let’s be blunt—scrolljacking is the design equivalent of taking the steering wheel out of a driver’s hands and saying, “Don’t worry, we’ve got this.” Except… the driver is your user, and they weren’t asking for a chauffeur.

Scrolljacking flips the script on one of the oldest, most sacred agreements in web UX: you scroll, the page moves—exactly when and how you expect.

It’s a contract born in the early days of the web, reinforced through decades of muscle memory, and enshrined in the unwritten UX constitution. Break it, and you break trust.

Why It’s More Than Just “Annoying”

When you hijack scroll behavior, you’re doing more than irritating people—you’re disrupting the control loop between human input and visual feedback. This is the same loop that governs video games, VR, even piloting a drone. Introduce a delay, force a speed change, or snap to an arbitrary point, and you’ve injected friction into a core navigational reflex.

Users feel this immediately. Their hands know what “one flick” on a trackpad should do. Their brains predict where the viewport will land. Scrolljacking says, “Nope, we’re doing my thing now,” and that disconnect isn’t just cognitive—it’s physical.

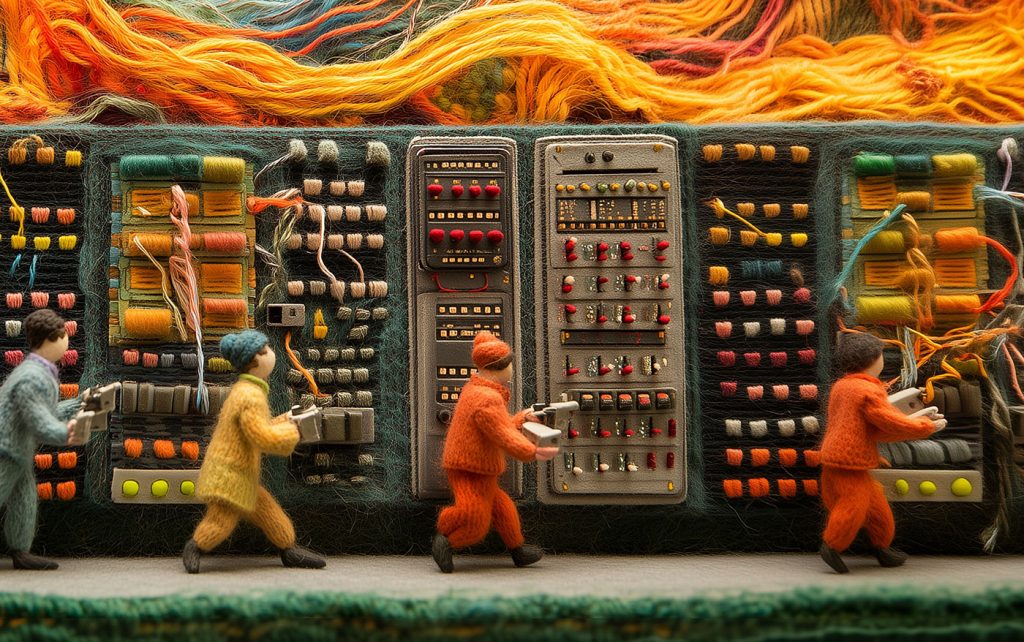

The Illusion of Cinematic Storytelling

Designers often defend scrolljacking as storytelling. The thinking goes: if we control scroll speed, animations, and section breaks, we can pace the narrative like a film. Nice theory. But here’s the thing: a web page is not a movie.

In cinema, the director always controls pacing. In web UX, the user does.

Scrolljacking is essentially saying, “We know better than you how fast you should read, process, and move on.” That might fly for a product launch microsite that’s more spectacle than substance. But try that on a documentation site, dashboard, or content-heavy page, and you’re actively degrading usability in favor of ego.

It’s a UX Anti-Pattern in Disguise

Some UX sins are subtle. Scrolljacking isn’t. It’s a classic anti-pattern:

- It overrides expected browser behavior.

- It ignores accessibility norms.

- It often breaks on older hardware or with assistive tech.

- It penalizes power users who skim, scan, and navigate at speed.

If you’re thinking “But Apple did it…”—remember that Apple also has the luxury of a high-friction walled garden where users tolerate quirks because the brand buys goodwill elsewhere. You? Probably not.

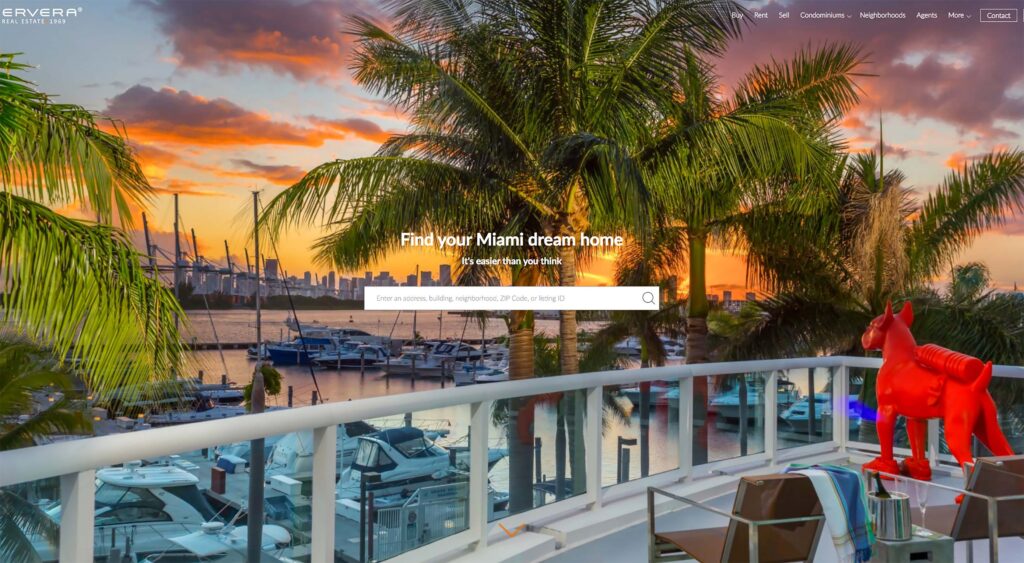

The Rise of “Soft Scrolljacking”

Here’s where it gets sneaky. Modern implementations don’t slam the brakes on your scroll—they feather the controls. They ease you into fixed-duration animations or snap points so subtly you almost don’t notice.

Think of it like lane assist in a car: you’re technically still steering, but the system is nudging you toward where it thinks you should go. This “soft scrolljacking” shows up in:

- Parallax reveals that require a fixed scroll speed to sync elements.

- Scroll snapping that jumps you to neat section boundaries whether you want it or not.

- Inertia damping that subtly changes your natural scroll momentum to match a design rhythm.

To casual users, it feels “smooth” and “polished.” To power users, it’s still an override—just wrapped in better PR.

And while it may pass unnoticed in portfolio sites or product teasers, it’s still risky in functional contexts. Even gentle control theft is still control theft.

When the Temptation Creeps In

Every designer has that moment. You’re building a visually rich page, animations in your head are choreographed to the scroll wheel, and you think, “This is going to be slick.” And it might be—on your high-end laptop, with your perfect internet connection, in your ideal browser.

But readers know: UX isn’t about how good it feels in the perfect conditions. It’s about how bad it feels when something breaks.

And with scrolljacking, something will break—touch devices, keyboard navigation, reduced motion settings, trackpad acceleration, you name it.

The Bottom Line

Scrolljacking doesn’t just remove control—it removes trust. And in UX, once trust is gone, no amount of animation polish will win it back.

You can still tell stories. You can still guide pacing. But do it through design that invites, not design that hijacks. Because the best interface is the one that moves exactly when the user says so—and no sooner, no later.